About Us

Stops & Shops

In The News

A treasure trove of riches off New Mexico highway

June 26, 2006

Stories and photo by Cynthia Pasquale

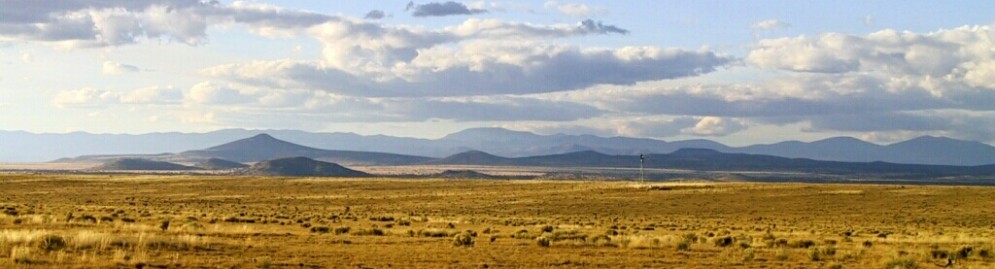

Many of northern New Mexico's "hidden" geological jewels – extinct volcanoes, lava flows, petroglyphs, sandstone formations – can be found just miles off Interstate 25, that long ribbon of blacktop connecting the state's most popular destinations, Santa Fe and Albuquerque.

Simply pull the pedal from the metal and veer off that 75-mph highway. You can step back in time to places not only beautiful, but wondrous.

These three I-25 side trips are only the beginning of what could be a long, delightful experience.

Nearing Raton, the landscape, celebrated for centuries in artwork, looks like Vulcan, the god of fire, shaped the bedrock of the state.

New Mexico arguably can be called the land of volcanoes, for within its borders are hundreds of examples of volcanic activity: cinder cones, lava flows, basalt mesas worn by wind and time. And because some are national monuments, visitors can get a close view.

About 30 minutes southeast of Raton, Capulin Volcano rises more than 1,300 feet above the grasslands. Besides its aged beauty, what makes this extinct cinder cone exceptional is that you can walk into its depths. Capulin is one of the few volcanoes in the nation with a paved road to its summit, and from there, a 0.2-mile paved trail leads to the bottom of the cone, right at the spot where this mountain was born.

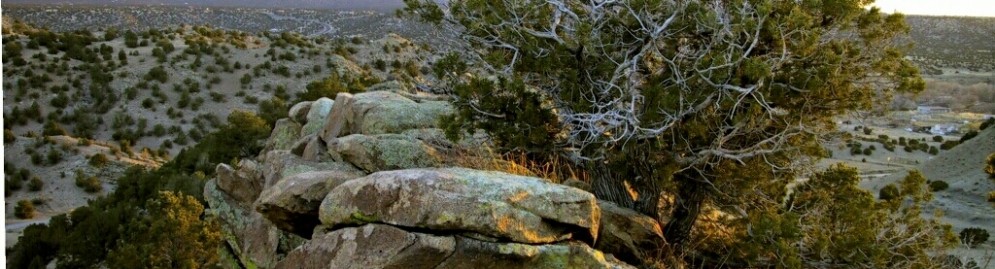

You also can walk along a path on the rim of the crater, where great basalt rocks are held together by the roots of pinyon and juniper trees, scrub oak and the mountain's namesake plant, chokecherry (capulin in Spanish).

The upside of this wicked environment is the view. Capulin is about midway in a volcano field that stretches from Raton to Clayton, near the Oklahoma border. The distant, grassy horizon is interrupted with peaks (snowcapped in spring), more cinder cones, lava-topped mesas and domes, and lava fields that stretch for miles.

Cultural magnetism pulls most people to Santa Fe. But once you're sated by museums, more than 200 art galleries, and plentiful restaurants, go south along New Mexico 14, a National Scenic Byway called the Turquoise Trail.

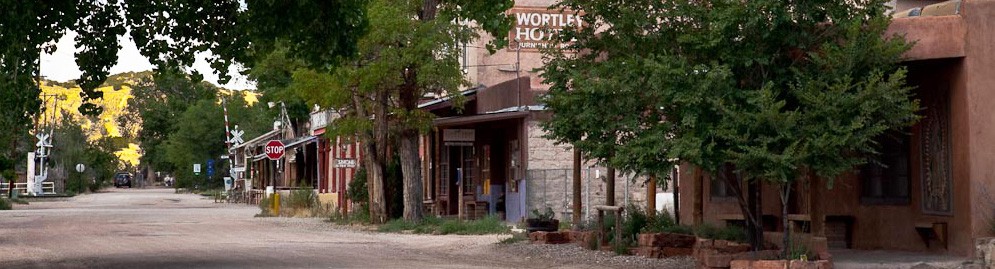

Several small villages dot this back road between Santa Fe and Albuquerque. The first is Cerrillos, famous for the mines that made this area prosperous.

The Cerrillos Mining District is most known for the turquoise found there. American Indians were the first to mine the semiprecious stone as early as A.D. 900, using rock hammers and chisels. It's estimated that hundreds of thousands of finished turquoise pieces were made from mines in this area, and many were traded to others all over North America.

Todd Brown has a claim just outside Cerrillos, near one of the largest and oldest mines in the area, Cerro Chalchihuitl. Brown and his wife also own the Casa Grande Trading Post, where he sells polished stones and a cornucopia of other items.

Down the highway at Madrid, a coal-mining museum documents boom and bust times. Most of the residents have left the past behind, refurbishing ramshackle buildings into 50 art galleries and coffee shops.

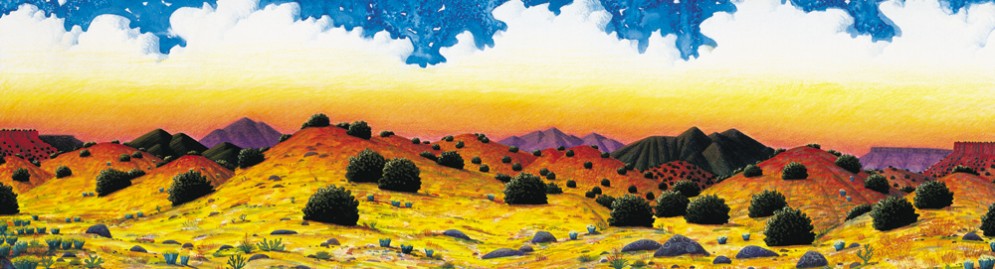

Past Madrid, it's the landscape that triggers drivers to stop for a gawk. The road continually climbs, leaving behind the low-slung pinyons and chollas for ponderosa pine. The Ortiz Mountains slowly fade in the rearview mirror as you approach the Sandia Mountains, so named by the Spanish because their ruby red color at sunset looked like sandia, or watermelon.

Other points of interest just off the Turquoise Trail via New Mexico 536 include Sandia Crest, the 10,678-foot summit of Sandia Mountain, where the observation deck offers information about the area and spectacular views; and the Tinkertown Museum, an animated, miniature Old West town and circus with thousands of hand-carved figures and antiques.

Back on New Mexico 14, the Museum of Archaeology and Material Culture covers an American Indian timeline, the impact of bison and turquoise on the area, and the Sandia Cave excavations.

More nods to volcanic times can be found west of busy Albuquerque on Interstate 40. Roads are cut through ancient lava flows, and mesas jut out like long fingers stretched across the prairie.

Basalt rocks were the perfect palette for the ancient Pueblo peoples there. Water and heat, mixed with minerals and bacteria, formed a glaze on the rocks' surface. People scratched or picked through this iron-colored layer, often called "desert patina," to reveal the lighter color below.

They documented everyday life: a maiden holding a corn stalk, men with bows and arrows; frogs and birds. They also documented the unknown and sacred: stars in the nighttime sky, masks, shamans, spirals, death faces.

More than 20,000 petroglyphs have been found at what is now Petroglyph National Monument. Short hiking trails lead visitors past many of these rock pictures, most 400-700 years old.

Continue west on I-40 to Grants, N.M., then veer onto New Mexico 53, called The Ancient Way. Here stretches El Malpais, which became a national monument in 1987. El Malpais, literally "bad country," is a series of lava flows that covers 590 square miles. Within this conservation area are the black, twisted remains of volcanic events, along with ice caves and sandstone formations. Various roads lead to some of the main attractions, or you can hike into the area.

An easier viewing prospect is the Bandera Ice Cave and Bandera Crater, which sit on privately owned land in the lava fields. The cave is a collapsed lava tube, which for centuries has trapped water that is then frozen by the constant 31-degree temperature. The cave's floor is said to be about 20 feet deep and shines green from arctic algae. You also can take a short climb to the rim of Bandera Crater, another large cinder cone and the genesis of a 23-mile long lava flow.

The property has been in the Candelaria family for three generations, and inside the trading post are Indian vessels and other artifacts dating back 1,200 years found in the flows.

A few miles west on New Mexico 53, an enormous sandstone formation attracted travelers from miles away because it protected the only sure water source in the area. As thirsty wanderers sipped, they also wrote, and the rock, now El Morro National Monument, soon became a public diary.

Ancestral Puebloans first inscribed images on the rock near the borders of the pond. In 1583, Spanish explorers were the first to record the rock's existence in their journals, but didn't carve their names. The oldest inscription is by Don Juan de Onate, who established the first Spanish settlement in the southwestern United States. His message reads: "Here passed by the Governor-General Don Juan de Onate, from the discovery of the South Sea, the 16th of April, 1605."

After scrambling over the rocks much like the ancients did during the 13th and 14th centuries, you will find the site of A'ts'ina, a settlement that probably was three stories high. It's unknown why the site was abandoned, but the people moved west and founded villages near the present site of the Zuni pueblo.

The experience and views are spectacular.

Construction Alert

Details about roadway construction on NM 14Upcoming Event

CrawDaddy Blues Festival

Saturday, May 17 & Sunday May 18, 2025The Mine Shaft Tavern in Madrid holds its Annual CrawDaddy Blues Festival. Great lively Blues!

Event details » View all events »